Episode 3: LGBT+ History Month and healthy ageing

10 February 2021 (updated on 10 February 2021)

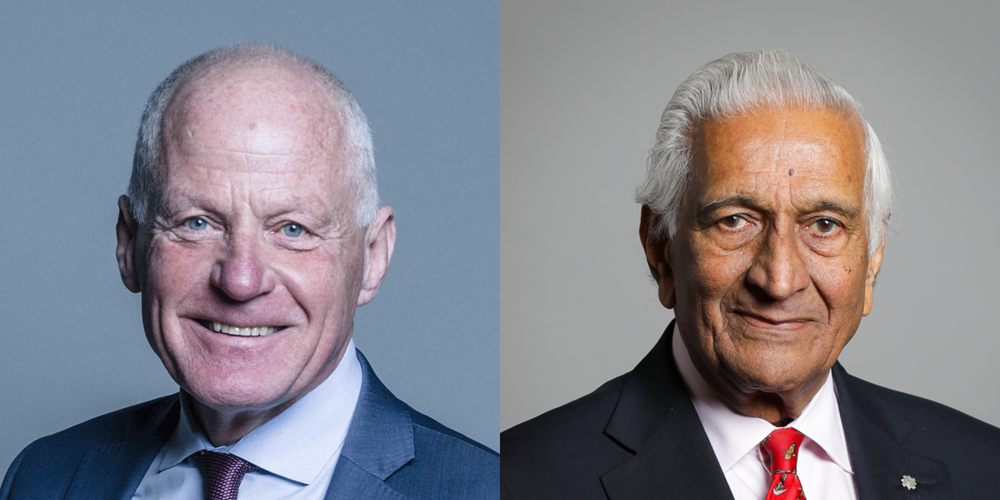

It's LGBT+ History Month in February and we are joined by actor, campaigner and politician Lord Cashman on the podcast. He talks about his life and journey to the Lords, fighting for equality and founding Stonewall with Sir Ian McKellen, and how he hopes to make a difference in the House of Lords. We also hear his thoughts on the new Channel 4 drama 'It's a Sin'.

We are also joined in this episode by Lord Patel, Chair of the Lords Science and Technology Committee. He talks to us about why the UK is missing its targets for health ageing and what more needs to be done to ensure we all live longer, healthier lives.

Plus Amy and Matt explore what has been happening in the House of Lords since we last met, including the recall of both Houses on 30 December to pass a new law in a single day.

Find out more about the subjects in this episode:

- Find out more about Lord Cashman

- Find out more about Lord Patel

- Read more from the Lords Science and Technology Committee

Transcript

Matt:

Hello, I'm Matt Purvis.

Amy:

And I'm Amy Green. Welcome to the House of Lords Podcast.

Matt:

In this episode, we're talking about what's been happening recently, the science of healthy ageing, and we hear from Lord Cashman about his life and campaigning for LGBT+ equality.

Amy:

Welcome back. It's been a while actually since our last episode. I think it was about a week or so before Christmas, which just seems such a long time ago. Should we kick off by talking about what's been happening since we last spoke?

Matt:

Yeah, sure. Well, the big thing was that there was a trade deal announced on the 24th of December. Then we had a recall of the House of Lords on the 30th December, that saw the House returned to pass a bill in a day. Since then on the 5th of January, the House has returned and has been sitting regularly since then.

Amy:

What exactly is a recall?

Matt:

Okay. Well, essentially a recall is when the House returns from a preplanned break in proceedings. Before Christmas, what happened was that the House adjourned on the 17th of December with a planned return of the 5th of January. That would be a normal Christmas recess but, of course, in the meantime, the government was negotiating with the EU to try and strike a trade deal. The House was told that the House may return if a deal was struck. That's what exactly was announced on the 24th of December. Obviously it wouldn't have been very popular to call the House back on Christmas day. The 30th December was earmarked and both Houses returned that day to sit, to pass the European Union (Future Relationship) Bill.

Amy:

How common is that? How common are recalls?

Matt:

Well, I've been looking at the figures and in the last decade we've had six. That's since 2011. Recalls typically happen in response to international situations, or notable deaths. In the last 10 years, the House was recalled following the murder of Jo Cox MP. When Baroness Thatcher died as well, the House was recalled for tributes. Up until 2011, there were five as well, but they all cluster around 2002 relating to 9/11 and the Iraq war. We then had none between 2002 and 2011. It was probably a little bit more unusual that the House came back to pass a bill in such a rush. That is probably fairly unusual. That was only a third time since the war that had happened.

Amy:

As you said, they met to pass the European Union (Future Relationship) Bill, which is obviously now an Act and they did that in a day. Doing all the stages and giving it Royal Assent in a day. How often does that, does that happen?

Matt:

It's not uncommon, but it requires for the House to agree to basically suspend its own standing orders or dispense with its own standing orders related to minimum intervals between the stages of bills. For instance, between a bill arriving in the Lords and it having its first substantive debate, the Companion to the Standing Orders - a rule book as to how the House operates - says it's two weekends between the two. Obviously the House has to dispense with that in order to do it in a day.

Amy:

That was December. What's been happening since the Lords returned in January?

Matt:

Well, as I say, the House has been meeting as normal. We have questions every day. There's private notice questions when the Lord Speaker approves them, scrutinizing legislation, debating committee reports, committees have also been releasing reports. Probably worth noting here, the International Relations and Defense Committee’s report on Afghanistan. We also have seen the Science and Technology report on the science of ageing.

Amy:

We spoke to Lord Patel who chairs the Lords Science and Technology Committee.

Matt:

He shared with us some of the recent work of the committee on the science of ageing and their recommendations to the government on how to improve health in older age.

Lord Patel:

My name is Naren Patel. I'm a member of House of Lords, I chair the Science and Technology Committee, and the inquiry on Ageing: Science, Technology and Healthy Living.

Matt:

Lord Patel, thank you very much for joining us.

Lord Patel:

Pleasure.

Matt:

Is it right that the Science and Technology Committee found that the government will miss its targets to extend healthy ageing by five years, by 2035?

Lord Patel:

Well, I need to put that question in the context. The context is this, that the government in 2017 announced as part of the aging society grand challenge, which was one of the industrial strategies, was to extend healthy ageing by five years beyond the current minimum now and to do that by 2035. Our inquiry exploring the science and technology that could help deliver on that found that in fact they will not meet that target for a variety of reasons. Therefore, we recommended that they should revisit that strategy and come out with a clear roadmap and have a person in charge to deliver on it with regular reports to Parliament as to how that strategy is progressing. I think the ambition is good to extend healthy aging by five years by 2035, even if it takes slightly longer.

Matt:

What role does inequality play in all of this?

Lord Patel:

That's a good question because, firstly, we found that unless we deal with inequality, and what do we mean by inequality? People who are less deprived and I use it deliberately, less deprived, live a healthier life by as much as 16 to 18 years longer than those of the deprived community. That's the key issue about inequality. Inequality, deprivation, leads to ill health and early death. The first thing we need to tackle, if you want people to stay healthier longer, is to tackle inequality in our society that increases ill health and early deaths by as much as 20%. That's what we mean by inequality. In fact, if I put it in the context of COVID, which is a question you might ask me, is that COVID has starkly demonstrated that. That it is the old and the deprived population - of course ethnic minorities too - but the aged and the deprived population suffered most particularly if you remember the data in the first wave of COVID starting in March.

Lord Patel:

COVID has put that into clear context. Not only that, but people who suffer ill health because of deprivation have what we call multi-morbidity. They suffer from multiple disorders and diseases. Again, COVID had starkly demonstrated that - the aged, the multi-morbidity, the ethnic groups and the old.

Amy:

What do you think the government could do to resolve these issues?

Lord Patel:

First and foremost, deal with inequality. We need to tackle inequality and deprivation to keep people healthy, to help people have a healthier life, and also have a healthier, longer life when they get older. There's also an issue that the people who are unhealthy and younger also become less productive. There’s an economic side to it too. This, plus the need to deal with inequality first, and deprivation. The second is about healthy living, which is a message that we are given all the time, not smoking, not drinking too much alcohol, taking exercise, keeping your weight reasonable, et cetera.

Lord Patel:

You young guys seem to be doing better than us oldies, but that healthy message doesn't seem to get across very clearly. We do say in our report, the government needs to find out why that message isn't getting out. Is it the way it is delivered? But the important messaging as it pertains to our report is that people that we talk to, need to be told if you live healthier lives, starting at a younger age, you will have a healthier old age. That's the important thing. But another important thing is about healthier lifestyle and old age is that actually it is demonstrated through cohort studies that it improves cognitive performance. Older people value cognitive performance. Because if your mind doesn't function and you can't communicate et cetera, then it makes you even more less of a social being. That message also needs to be reinforced.

Lord Patel:

We now know a lot about the science and the biology of ageing, which we didn't know before. As we age our cells, for instance, don't die, they survive and they become what is known as senescent. When the body's cells become senescent and they accumulate, they set up an inflammatory process. That inflammatory process results in diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, blood pressure, cardiac disease, diabetes, even possibly Parkinson's and Alzheimer's. What we need now is developed diagnostics that will signal earlier on that you are getting accumulation of senescent cells, and then find treatment - drugs to mitigate against it. That is already happening. That we're beginning to use, identify some new drugs and some drugs that already exist that may help mitigate against this process so people don't develop these diseases.

Lord Patel:

The science of ageing and the biology of it has a great promise to keep people healthier longer and find diagnostics and medications that will help. What we need is greater resources towards research in this area. That too will help significantly around avoiding people developing multiple morbidity and living healthier lives. That's extremely important. After all we're the Science and Technology Committee and the science and the study of it is important. That is a key area.

Amy:

That's really interesting so it's fundamental to ageing then?

Lord Patel:

Yeah. What we now know in a cell cycle, while you are talking to me, millions of cells in your body - and mine - are dying off. In your case, cells are dying off and they're gone. In my case some of them, they don't die off, so they accumulate. When you accumulate, and that key biology that I was taught in medical school of any disease, is that you get an inflammatory reaction. You're more familiar with acute inflammatory reaction when you cut yourself or get hurt or break a bone, and it hurts and gets inflamed. But what I'm talking about is a chronic inflammatory condition. You don't see that redness but these cells set up an inflammatory reaction. The fundamental basis, pathological basis of any disease is an inflammatory process that then results, depending upon where it is.If it's in a joint, you get arthritis. If it's in your blood vessels to get blood pressure, if it's cardiac, then damages the cardiac cells, damages your kidneys. If it's in your brain, you might get Alzheimer's or Parkinson's disease.

These senescent cells that accumulate, we need to either find a way to identify early accumulation and kill them off, which would be ideal, or reduce the numbers or manage them to become less inflammatory. That's when the drugs will come in. Already there are a couple of drugs on trial, and that's an important issue. Most trials of drugs are done in a pure situation. They're not done in people who have multi-morbidity to treat multi-morbidity. There are other issues about how we look after people with multi-morbidity, but that science is quite fascinating, which we didn't know 10 years ago.

Lord Patel:

Now I think, we haven't talked about technologies that will be needed to help people live more independently in older age, such as AI and robotics, et cetera. It's possible to monitor me if I was living alone, remotely with AI, so that somebody doesn't have to sit watching me all the time to live more independently. You might not know yet, but I do, even a simple gadget, like a bit of rubber that makes it easier to open cans. We'll also get embedded diagnostics so you can monitor people's diseases and treat them. We use it in my hospital here, actually. They're not embedded yet, but they are through your phone or whatever.

Matt:

Lord Patel, you mentioned earlier about healthy lifestyles and I just want you to ask your view on habit forming behaviors right now during lockdown. Any day of the week, you open the newspaper and there's something about increasing alcohol or people not exercising as much. Do you have any concerns about the longer-term implications of that for healthy aging?

Lord Patel:

Well, the concern I have is not about lockdown. It's not just about the older people. It's about virtually children to older people. That concern to me anyway is not so much about the amount of alcohol they might be drinking, which I think people probably are drinking more. I think people are taking a bit more exercise than they normally used to because that's the only way to get out. But more concern I have for all age groups is the mental health.

Amy:

What's next for the committee?

Lord Patel:

Apart from health and COVID, which is our current problem, some people will say that the bigger problem is climate and environment. We’re going to look at the science and technology of de-carbonization. We are going to look at the major areas which we can decarbonize like transport or home heating - can we deliver it using technology at scale? Just like can you deliver good health at scale and what might be the cost? We're going to look at some aspects because we can't do it all, some areas of science and technology of de-carbonization and can it be delivered at scale, whether it's hydrogen, or batteries or carbon capture or carbon air capture or home heating or air or ground heating or whatever. That's next.

Amy:

Lord Patel, thank you for joining us. It's been really nice chatting to you today.

Amy:

Next up it's LGBT+ history month at the moment. The House of Lords is celebrating our LGBT+ members and their contribution.

Matt:

Lord Cashman is known to many people as an actor, famous for a number of roles, including Colin Russell in EastEnders. He also co-founded Stonewall and sat as an MEP for 15 years.

Amy:

We spoke to Lord Cashman about his different careers, what brought him to the House of Lords, and where we are now with LGBT+ equality in the UK. Here's what he had to say.

Lord Cashman:

Hello. My name is Michael Cashman - Lord Cashman of Limehouse - but I prefer to be called Michael.

Amy:

Michael Cashman, thank you for joining us on the podcast. It's currently LGBT+ history month at the moment throughout February and your book, ‘One of Them’, tells your incredible story from growing up in the East End to joining the House of Lords through some of the most pivotal moments in contemporary gay history. Growing up, did you ever even imagine that you'd find yourself where you are today?

Lord Cashman:

No. I live very close to the big, huge council state where I grew up in the East End of London. The thriving docks that were just alive with energy and goods coming from all parts of the world and being shipped around upriver, downriver, disappearing into men's pockets and trousers. Often, I used to play with my brothers on the river, doing things that if we did it today, our parents would get locked up. Jumping at high tide from barge to barge, going into warehouses and out onto the Thames as the tide was coming in and going out. Often, this is absolutely true, I walk on my way to work and I sometimes visualize that five-year old me, down on the beach or jumping from barge to barge. The holes hanging out of his trousers, holes in his shoes, socks that would never stay up.

Lord Cashman:

I look at him and I think what an amazing journey and I could never have imagined it. Unimaginable. Interestingly, you mentioned the book. When I physically collected the book just before it went on sale. I got it and came home. Walked along Narrow Street and there down this little side street where I used to run and play. I saw the young me running along that street and I began to cry because I thought of the amazing journey that I'd been on and that I'm still on. It was all there in this book under my arm. The dark bits, the brilliantly light and funny bits, but it was all there. I don't take it for granted because it's still forever around me. Also, what I do know is that whatever you have, you can always lose.

Amy:

Absolutely. God, I think that it's the most beautiful answer we have ever had mentioned in the podcast.

Lord Cashman:

Well, it's downhill from here.

Amy:

Many people of course will know you from your career as an actor, but also as the co-founder of Stonewall, the campaigning organization that you set up with Sir Ian McKellen. What led you to that?

Lord Cashman:

The really interesting thing is going back to the origins that we talked about. That really all of the this happened by a series of accidents or things that I shouldn't have dared to do. The fact that I failed my 11+ and ended up... Failed something I didn't even know I was taking, but ended up at a secondary modern school where, because I knew at the earliest age, I was attracted to boys, sexually - we used to call it queer. The fact that I knew I was gay and I didn't belong, I found an outlet and that outlet was singing, dancing, and impersonating. Because I impersonated Eartha Kitt, and found this amazing world at school behind that faded red curtain where I could be different and I could belong, and I could have all of my different characters enter my pretend world.

Lord Cashman:

It was through impersonating Eartha Kitt, singing in the end of term school show, that at the age of 11, I was invited to go and audition for ‘Oliver’ in the West End and my life changed. That took me on this arc all the way to where I am now with various diversions. The straightforward answer to setting up Stonewall, my career, I had very different, some amazing changes at the height of success. But there I was starring in the most popular show on BBC television at the time, EastEnders. We used to get between 11 and 17 million viewers every episode. When I was playing Colin, the first time a gay character had been portrayed in a very ordinary non-stereotypical way. It was greeted when I went on with huge controversy, media outrage, outrage in parliament, because the AIDS pandemic was something that we were living with.

Lord Cashman:

During my time on the show, the conservative government led by Margaret Thatcher, introduced the first anti lesbian and gay and bisexual law in a hundred years. I knew I had to be a part of that group of people campaigning against this law. It was an amazing campaign. It became law. We lost the battle. Having lost the battle, I said to Ian McKellen that we should set up an organization so another Section 28 never happened again. We'd won the arguments for equality, and we should continue to win them, to place them, and make them non-party political. That was 1988 and a year later, we publicly launched Stonewall. Our remit was equality and social justice for lesbians, gay men and bisexuals. It was only much later that we took on the very important issue - and I'm proud we have - of the rights of trans people. But the very beginning, 1989 and the quest, the simple quest, equality before the law and the equal protection of the law.

Amy:

I suppose that sparked your involvement in the political world. You later became an MEP and you've played key roles in the Labour Party. In fact, I know your civil partnership was attended by about half the cabinet at the time, and your friends from TV and theatre. You've had a lot of different jobs in different industries and very different worlds, what has it been like straddling between the arts and the political circles?

Lord Cashman:

Well, what is interesting is I joined the Labour Party... My dad was a docker. My mum was a proud office cleaner. I used to go office cleaning with her as a kid. My roots were rather like my father's. He was a trade unionist. I joined the Labour Party when I was 25. But I never thought that I could go into politics. I hadn't finished my education. I left school really, at the age of 12. Yes, I did sciences a bit later in my life because I wanted an amazing career change, which people will have to read about. But when I made that decision, encouraged by the first woman general secretary of the Labour Party, Baroness Margaret McDonagh as she now is and with the love and support of my late husband, Paul. They convinced me I could do it.

Lord Cashman:

I stood for the national executive of the party. Then as you say, became a member of the European Parliament in 1999. The first time that someone had been elected, who was openly gay from the United Kingdom to the European Parliament. Straddling those different worlds, they're quite complementary because first of all, you have to mean what you say. If you mean what you say, you can communicate it. If you don't mean what you say, the public hear it immediately, they hear it in your tone. People recognize nonsense quicker than they do sense. Being aware of communicating your message, learning your brief, knowing your brief, and also having the courage to say when you don't know the answer, when you're in territory that you're not sure of. As an actor, you're always taught to experiment, to imagine, to look at it differently, and to work with people. This is crucial.

Lord Cashman:

I think in politics, politicians far too often own the success. I believe, as politicians, we should say, the success is brilliant and we all own it. That the constituent that brought it to me, the company, the person, whatever, my staff, the people who work with me. Another mantra of mine is I don't work for anyone. Nobody works for me. I work with, they work with. We are on the same level, the same landscape. The European Parliament helped me as a kind of training ground for what it's like in the House of Lords. In the European Parliament, no one party has a majority.

Lord Cashman:

You have to work cross party to get that majority. You have to compromise. Compromise being a positive notion, not a negative notion. That's very much the way the House of Lords works. You can win the arguments in a debate on an amendment. You build up relationships, personal relationships, political relationships, across the different parties. I love that way of working. I think the fact that I'm free in that comes from an artistic background where you've got to work with others, sometimes even if they don't like you and you don't like them. It's the outcome that matters.

Matt:

Michael, you've led a lifetime of firsts and you've mentioned some, the first openly gay person to be elected a UK MEP, famously shared the first gay kiss on a UK soap. You also helped to drive forward an end to the ban on gay people serving in the armed forces and the creation of civil partnerships as well. Where do you think we are right now in terms of LGBT+ rights and equality? Do you think the progress is under threat?

Lord Cashman:

We're in a worrying position. I see that with the defamation, the demonization of trans people and trans women in particular. The fact that we still haven't had the promised ban on conversion therapy, and there are talks that, from within number 10 Downing street, there is a resistance on that. The promised reforms on the gender recognition act and the defamation of trans people. That's also impacting on LGB plus people, non-binary, intersex. Why am I worried? I am fearful that we have created scapegoating, the fear of the other that somehow other people are to blame for problems that occur in this country or in our neighborhood, or in our locale. Absolutely not. That notion builds on taking away the rights of people, whether they're people who have the right to seek asylum - I believe in refuge. On Holocaust Memorial Day, at night, I light a candle and I stand in the window as a sign that there is refuge here for those need it. How does intolerance and hatred begin? It begins when somebody decides to extinguish that candle and look away.

Lord Cashman:

I am worried and I've seen sadly in the House of Lords, trans people and trans teenagers and their families completely misrepresented. Now I see the attacks on lesbian, gay men and bisexuals. I see the attacks in our schools where the DFE for three years worked on guidance for inclusive relationship and sex education, remembering that education empowers young people. Suddenly, without any reference to the teachers and the experts that they've been dealing with, the guidance was changed and fudged, but only around LGBTI issues. A very dangerous signal and very worrying.

Matt:

We talked earlier about campaigning for equality. You mentioned some issues there in terms of LGBT+ rights and equality. How do you think your campaigning methods have changed since joining the Lords? You mentioned earlier about cross-party working. Has it changed at all? Is it the same techniques?

Lord Cashman:

It hasn't changed. If I'm honest, I've just elided from my 69th year into my 70th. Sometimes you get a bit tired that having to fight the same battles 30 years later. We're literally fighting the same battle against section 28. They don't want to talk about these things in schools. I've already talked about that a little, but my campaigning techniques haven't changed. You have to put the reasoned and reasonable arguments for doing the right thing. You have to work cross party. For instance, I do a lot of work with Baroness Williams, the home office minister, Lord Lexden, and I've just worked with Baroness Goldie on the Armed Forces Bill, which was introduced into the other place, the House of Commons this week. Within that bill, there are changes that I've been arguing for, and that are currently in my private member's bill, extending posthumous pardons.

Lord Cashman:

That's the same way we started with Stonewall, which is to say campaigners, and campaigning organizations always have difficult lives because that's the nature of arguing for change that there is a great resistance to delivering. But it goes on and I'm deeply empowered by the fact that there are young people behind me with energy. The young people are ahead of the game on issues around gender identity. I've always said that the most terrifying sound that a despot, or someone who's intolerant or resistant to change can hear is the sound of a newborn baby, because it signals another generation has come and another generation will come after that.

Matt:

In joining the Lords, I'm thinking that your answer might be no here because it's ongoing goals, but did you join the Lords with a specific goal in mind?

Lord Cashman:

When I joined the Lords, of course, the then leader of the Labour Party, Ed Miliband had named me as the first ever global envoy for LGBT+ issues. I often reflect that if Labour had won that election, I would have been the global envoy without a credit card going around the world, making the case for change and apologizing for the negative changes that we forced on countries during our colonial years. But going into the Lords presents me with other opportunities. The great thing about the Lords is regardless of whether I sit now as a non-affiliated peer - I resigned from Labour over antisemitism and Europe - but even if you’re sat as a party member, you're still an individual voice. You bring your experience, your expertise, your point of view.

Lord Cashman:

That's extremely important. The Lords gives me a lot of other opportunities, not the least on issues around defending human rights, defending the Human Rights Act. Issues on Europe, and particularly around ensuring that we, in terms of what we call the disregard of convictions for crimes that are no longer homosexual crimes, that we widened that disregard so that the records that people have are wiped clean and they can get on with their lives and do the jobs that they really want to do. It's a long way round of saying I love being in the House of Lords.

Matt:

Which brings us on to a related question that I get to ask in this podcast. We ask every member this one. Do you have a favorite moment so far from being a member?

Lord Cashman:

I do. I'd spent the morning. I think it was a Thursday early afternoon debate. I'd spent the morning with my brother when he was going through a three-hour disability reassessment, which was just, for me, unbearable. There, everything he said was punched into a computer and the computer makes the decision on his future. I was taking part in a debate around human rights. I thought I haven't got time to get upstairs for my notes. Oh, what should I do? I thought. I know what I'll do. I'll do the old trick. Sit there and then as soon as it comes to my turn, I'll stand up and say “My Lords, I have listened to the contributions of other noble Lords. It's quite clear that what I was going to bring to the debate has already been covered so I will retake my seat.” Thereby gaining a lot of brownie points from other people who want to speak.

Lord Cashman:

As the debate went on, the strands of what I prepared were coming back into my mind. I was being agitated by certain things that the government minister was saying. I stood up and I did my 10 minutes and I did it without any notes. I'm not boasting, but I blushed with some of the lovely comments that were made, and by people I really admire, that it should be read as a standalone piece, blah, blah. When the debate finished, I was walking along one of the corridors at the side of the chamber and a Law Lord who took part in the debate came towards me, really a wonderful man. He looked at me and he went, "Stole the show dear boy, stole the show." I said “It's not a show,” and he said “Sometimes it is you know, but you stole the show.” It was just lovely and warm.

Lord Cashman:

Actually, the day I went in, I was introduced. It was four days after Paul had died and the kindness and the empathy that I was shown was nobility itself. That's what I like about the place. It works out of mutual respect and respecting differences, as well as respecting agreement. Yes. There need to be reforms. Of course, every great institution must always embrace change and reform. But would I reform it with a directly elected House? Absolutely not. It doesn't need to look over its shoulder at fear of revising something that might make it unpopular. For me, becoming a politician at the top of the job description should be the courage to be unpopular because it means you will have the courage to serve the long-term not the short-term.

Amy:

Yeah. As Matt said, we tend to ask all of our guests that question. I love asking that one, because you just get such great stories and insights. It's actually interesting that a lot of you talk about each other and that working together and working with people that you'd never expect that you would work with.

Lord Cashman:

It works because I think the difference between our place and the other place as we call the Commons is that we start off by trying to seek agreement. It's a completely different mindset. Also recognizing that where there is disagreement, actually, as I mentioned earlier, you can overcome it, Amy. You can reach and say, “Okay, how can you and I, or us, how can we do this?”

Amy:

One of the shining lights really is that healthy debate that is really allowed in the House of Lords.

Lord Cashman:

Amy, also making party political points in the House of Lords, it doesn't go down well. I said earlier, I don't believe in having a directly elected - an indirectly, as part of the makeup of the House would be a very good idea. As an example, you're the leader of Leeds City Council, that gives you a right for you during your tenure and a year after to sit there in the Lords to bring in that huge experience of Leeds and that part of West Yorkshire but equally around the rest of the United Kingdom. But then you would have people who were appointed because I sit there in some debates that I'm not taking part in, and I'm in awe of the expertise that is being used to shape and refine and better legislation. Actually, it's expertise that the government could not buy. When I listened to some of those lawyers, those academics, people who come with the experience of their field, it's a huge asset for the country.

Matt:

I was interested about your moment of speaking without notes. Obviously as a very talented and experienced actor, I would have thought that would sort of always be second nature to you. You'd learn the speeches and perhaps go noteless. But I suppose my question is around what advice you were given when you first joined the Lords about how to make an effective contribution in the House. Also, what have you observed about what works and what doesn't perhaps?

Lord Cashman:

The argument about, do you stand up and speak without notes or not? Notes are a powerful tool to remind you that there are certain things that you need to say, certain points that you need to make. Also, Matt, to be honest, as an actor, when you get it wrong, it's you and maybe the production that suffers. In politics, if you get it wrong, it's the issue you're representing, the people who work with you and if you're in a party, it's the party that gets the blame as well. Interestingly, I don't believe in the concept of failure. I think it's something that's used to prevent people from taking chances. What other people call failure is for me, evidence that someone has tried to change something and presumably change it for the better. But when you do get those moments, those flights of imagination, where you pick up a theme and you run with it, it can be wonderful. But sometimes you run with it and then you don't know where to end with it and you see people turning off.

Matt:

… give up while you're ahead.

Lord Cashman:

Exactly.

Amy:

I was about to say exactly the same thing Matt. In a slight gear shift, I suppose, I'd like to ask you if I may, about It's a Sin. For anyone that hasn't heard about it, firstly, where have you been? But it's a series on Channel Four at the moment by Russell T. Davies, following the lives of a group of gay men, gay friends during, during the AIDS crisis.

Lord Cashman:

Amy, I sat down on Saturday after the Friday first episode went out and I thought, right, I'll watch it. I had messages from friends saying, ‘Oh, I watched the whole thing on All Four’. I thought people have got no taste, why gorge on something.

Amy:

That's what I did, sorry.

Lord Cashman:

I sat there and went through them all. It is an amazing piece of storytelling. Russell T. Davies, his writing is brilliant because so quickly you get to like his main characters and therefore you want to go on their journey. You hope for them, you empathize, you ache for them, and you hope it doesn't go where you think it might. I'm just about to pen a piece for a daily newspaper, actually, in that at the end of it, I had this clash of emotions that... I don't want to give anything away to those who haven't seen it all by the time we do our podcast, but I had that sense of loss at the end. But I also had this amazing anger because I realized that all of the stigmatization, the discrimination, the misinformation, the misrepresentation around LGB people, mainly gay and bisexual people - and AIDS and HIV from people who knew better and the media who knew better - was now being visited on trans women and trans men and trans teenagers.

Lord Cashman:

The fact that it was being done by some people, some activists who'd survived that crisis made me so angry because I thought, ‘have you learned nothing?’ We don't go through battles and have our scars in order to make sure that other people battle and other people have to carry scars, we go through those events and those challenges so that other people don't have to. I spoke to a group of headteachers yesterday on Zoom. I said to them that this should be shown every week in schools, because it's also a reminder about evil that is done when good is not heard or spoken of. Shakespeare brilliantly said, and that anti-gay, LGBT law, all those years ago, Section 28. Shakespeare brilliantly said ‘the evil that men do lives on, the good is often interred with their bones’, and I'm afraid that is true.

Lord Cashman:

Unless we challenge it and recognize that what is happening to another could happen to us, then evil will repeat itself. The show is a powerful reminder that you cannot remain silent on an issue. I deal with this in my book. I say about when Paul and I went back to New York and the places where we sought fun and refuge, you could no longer seek refuge because there was death in the corner. There was death in the face of somebody sat the other side of the bar. ACT UP, the American activists had a brilliant phrase. It said, ‘silence equals death.’ An important reminder, you cannot remain silent.

Amy:

I won't say anymore because I can't put it any better than that. I think we'll leave that one there. That was absolutely brilliant to hear your thoughts on that.

Lord Cashman:

Thank you.

Amy:

That's it for this episode of the House of Lords Podcast. Thank you to Lord Patel and Lord Cashman for joining us.

Matt:

If you enjoyed this episode, please subscribe and leave a review wherever you get your podcasts. If there's something you'd love us to feature in a future episode, you can tell us by tweeting @UKHouseofLords using the hashtag, #HLcast.