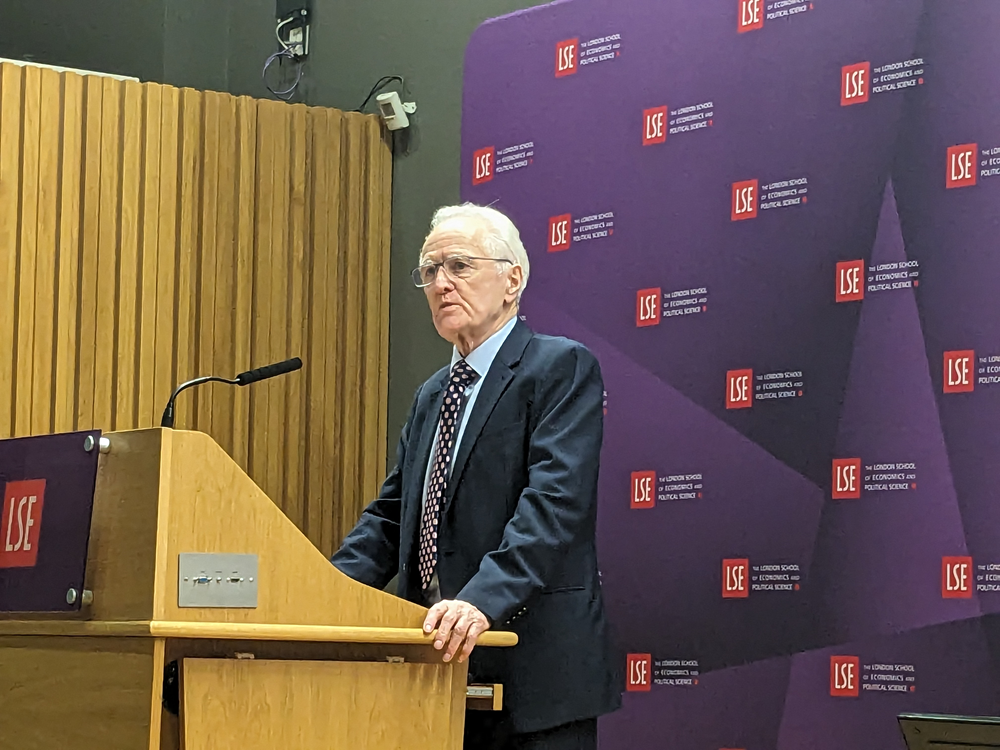

Speech to the London School of Economics

Lord McFall addressed the London School of Economics on 20 November 2023 in a speech setting out how the House of Lords uses a learning-based approach to dealing with the problems of the modern world.

Here is the text of Lord McFall's speech:

It is a privilege to speak at a university with such a proud tradition of learning and innovation. My respect for the London School of Economics is in part inspired by the work of William Beveridge, who was your Director and authored the eponymous report which built consensus on the role of the State in post-war Britain.

In addition, I respect those who work in education because I am one of them.

Although I left school early, I qualified through adult education, entered teaching and was a Deputy Headteacher when I was diverted into my political career.

I have never lost my passion for learning. I want to use this evening’s talk to explore how the House of Lords addresses some of the most pressing problems of our era by learning, by reaching conclusions based on facts and objective analysis and by using what it has learnt to build consensus.

If your understanding of politics is based on media representations of Parliament, you may be surprised to hear the words “learning” and “objectivity” mentioned in the same breath as the House of Lords.

A quick flick through recent clippings finds headlines like “The Lords have got to go!”, “Absurd aristocrats” and “Cronies lording over us all”. Media coverage focuses heavily on controversy around appointments and individual members’ alleged misdemeanours. Commentators regularly trot out demands for abolition, as if this could be achieved with no loss to our system of government.

But there is little or no reporting of the work which is actually done in the Lords, and little analysis of whether radical reforms - such as the election of members - would improve the way law is made in our country.

I have sympathy with calls for change in structures and in culture. In my non-party role as Lord Speaker, I cannot campaign for a particular reform agenda. But I believe that anyone wishing to sweep away the existing system must take a long hard look at what the House of Lords does and answer the question of whether its work could be replicated under an alternative framework.

Looking firstly at the work of the second chamber, I believe the House of Lords makes three distinctive contributions to the political process:

First, we debate extensively the really important issues.

Second, we bring genuine expertise to bear

And third, we conduct ourselves with respect for all.

What are the really important issues that Parliament needs to discuss? You could probably reel off a list – climate change, economic instability, migratory pressures, new technology. I think many of them can be boiled down to what I call the “Four Ds” – Demographics, Data, Decentralisation and Disorder.

• Demographics – Our population is getting older. That is a wonderful thing, but it means increased demand for pensions, healthcare and social care. It means an increased burden on a smaller workforce of younger people who find themselves excluded from the access to housing, early retirement and generous pensions that were available to their parents’ generation.

• Data – The internet has been predominantly a force for good in our economies and in social connection, and AI promises further benefits. But both also bring big challenges – whether threats to jobs; mental stress caused by social media; loss of privacy and security; or “fake news” undermining trust. New technologies have fuelled the emergence of the ‘Three P’s’ in politics – populism, post-truth and polarisation.

• Decentralisation – People rightly expect more say in their lives, and our centralised system faces pressure for the devolution of political, economic and social power. While the rising cost of living in our capital has made it more attractive for many young people to build their lives and careers elsewhere, London still holds sway over much decision-making for other parts of the UK.

• Disorder – Over the last 30 years, many of the anchor-points that ordered the world of the late 20th century have been uprooted. The market economy has struggled to deliver prosperity since the financial crisis of 2007. Capitalism is no longer seen universally as the ‘rising tide that lifts all boats’. The basic necessities of life have become unaffordable for many.

Recent years have witnessed a retreat from globalisation, a return to protectionist policies and the re-emergence of armed aggression in Europe and conflict in the Middle East.

We have moved from a bipolar world order to a multipolar world with the rise of the Global East and the Global South. Tomorrow we welcome to Parliament the President of the Republic of Korea, a prime example of a state which has undergone a transformation from poverty to economic power and influence in a few short decades.

These four clusters of challenges are shaping the world our young people will live in. Their complexity means we need a learning approach, constantly assembling and analysing new information to construct an understanding of a world in flux. And we need an engaging approach, bringing people together to build consensus for action.

These are approaches taken in the House of Lords, which brings together some of our nation’s finest minds to consider the thorniest issues away from the frontline of political battle, with the aim of reaching conclusions which can command consensus.

Foremost in this endeavour are our committees. The Economic Affairs Committee recently reported on the impact of demographics, Covid and retirement trends on the UK workforce, under the title “Where have all the workers gone?” It is now conducting a thematic inquiry into the Bank of England, asking whether the goals and tools it was handed when made independent 25 years ago remain appropriate in today’s world of inflation volatility.

Other committees have investigated how Government can ensure a resilient and affordable energy supply during the transition to net zero or how we can draw up new rules to govern the use of AI in warfare.

The Lords also plays a crucial role in what many would see as Parliament’s most fundamental task – setting down the law of the land. Largely away from the spotlight of publicity, the second chamber works doggedly on the exacting task of scrutiny and revision to ensure that legislation works as intended.

Bills frequently arrive in the Lords in an incomplete state, with important detail yet to be filled in. The time for debate in the Commons is closely controlled by the Government. MPs receive strict instructions from whips on how they should vote. With much of their day taken up by constituency work, campaigning and the demands of 24-hour media and social media, many have little time for close examination of legislation.

It is when a bill is in the Lords that the real job of line-by-line scrutiny happens. Unlike the Commons we have no guillotine on debate and no selection of amendments. Discussions continue for as long as it takes and no aspect of legislation is too obscure to be examined. There is no overall party majority, so ministers must proceed by persuasion rather than force of numbers.

This scrutiny has a real effect on the laws which are passed by Parliament. In a typical year there are more than 1,000 amendments made to Government legislation in the Lords. There were more than two and a half thousand in the session just ended.

About 100 of these each year are the result of Government defeats in Lords votes. These upsets grab most of the media headlines, despite the fact that many of them are subsequently overturned in the Commons. But a greater impact is arguably made by the thousands of amendments which are passed with Government approval, many of which represent a minister listening to concerns and objections raised by peers and revising plans in response.

It is in this way that the House of Lords deploys its independence and expertise to address the most important long-term issues facing the UK and build consensus around a way forward.

In his recent book How Westminster Works and Why it Doesn’t, political commentator Ian Dunt describes the Lords as “one of the only aspects of our constitutional arrangements that actually works.” And he states that it is the independence and expertise of the second chamber that make it so effective.

• What do we mean by independence? No party has a majority in the House of Lords and a quarter of members are non-party Crossbenchers or non-affiliated peers. Even members belonging to a political party have a measure of independence because they are generally not seeking promotion. These facts combine to make the House a forum for independent thought by those who have already achieved distinction in their careers.

The red benches are home to eminent figures from all corners of the UK’s public life. Scientists, doctors, captains of industry and leaders of trade unions. Campaigners for civil liberties and disability rights, environmentalists, academics and engineers. Their presence is a reflection of the fact that the life of the nation does not reside only in political parties, but is also expressed through institutions and organisations of many kinds.

• This diversity feeds into the expertise of the House. The Lords offers a powerhouse of knowledge and experience that any private consultancy would charge huge sums to access. The Economic Affairs Committee boasts former Bank of England Governor Mervyn King, ex-Cabinet minister Helen Liddell and Treasury permanent secretary Andrew Turnbull. The European Affairs Committee is chaired by former National Security Adviser Peter Ricketts and includes David Hannay, once the UK’s permanent representative at the United Nations. Former MI5 Chief Eliza Manningham-Buller has been an active member of committees on security and technology.

Some suggest that ministers get an easy ride in the House of Lords. Let me tell you that nothing could be further from the truth. One former minister who served in both Houses told me the experience of being questioned by peers is much more daunting. In the Lords, grillings are administered by former secretaries of state and leaders of the civil service, judges, ambassadors, European commissioners, ex-heads of bodies like Nato or the Joint Intelligence Committee. These are people who know their subjects intimately and can cut straight to the nub of any issue.

The House of Lords has been described by constitutional expert Professor Philip Norton as “an arena for the discourse of civil society”. Its ability to draw on the talents of those at the pinnacle of so many spheres of human activity is a precious resource which should not be squandered.

When I say these words, I am forcefully reminded of the example of my dear friend and colleague Igor Judge, the former Lord Chief Justice who sadly passed away this month. Until earlier this year, Lord Judge was a constant presence in the House, diligently examining the detailed wording of bills and drafting crucial revisions which were accepted by the Government as improvements to the law.

Another aspect of the second chamber which should not be diminished is the civility of its proceedings. Voters whose only exposure to Parliament comes from TV coverage of Prime Minister’s Questions might be forgiven for thinking that Westminster is a rowdy place, characterised by point-scoring, putdowns and fractious disagreement.

They would be surprised to learn that the House of Lords rarely hears a raised voice! We pride ourselves on conducting a courteous conversation allowing members to disagree agreeably. I believe this provides a pattern for respectful and reasoned debate in a public square increasingly dominated by tit-for-tat slanging matches.

This brings me to the question of reform.

I freely acknowledge that we would never create an Upper Chamber this way if we were starting from scratch. But we are not starting from scratch, and history shows that progress can be made by improving on existing structures, while wholesale change must be treated with caution.

We have twice made significant but incremental reforms to the composition of the House. The introduction of life peerages in 1958 revived what had been seen as a moribund assembly, adding individuals with extraordinary capabilities and experiences. The removal of almost all hereditaries in 1999 gave peers further authority to challenge Government legislation.

In contrast, attempts at radical overhauls have run into the sand. The Labour administration of 1968 attempted to introduce a permanent Government majority in the Upper House. In 2012, the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition tried to create an 80%-elected House with 15-year terms.

They failed because they lacked consensus and clarity about the nature of proposed new arrangements.

More recently, the prospect of an elected House of Lords or Senate has again been revived – but I know the same questions will come back: What powers will the new chamber have and how will differences with the Commons be resolved?

As things stand, the elected House rightly exercises primacy within Parliament. Peers regularly ask the Commons to think again on legislation, but the elected House usually has the final say and the process almost never ends in gridlock. Would a partially or wholly elected Upper House be so ready to accept the will of MPs?

Would an elected Upper House attract members with the experience, expertise and independence of the Lords? Would its members be ready to undertake the painstaking work of scrutiny and revision which acts as an essential check and balance on the elected majority?

While I defend the role of the House of Lords, I believe it is also clear that reforms are needed: NOT reforms of our powers or procedures. BUT reforms to our size, composition and appointment.

Both my predecessor, Norman Fowler, and I have been at the centre of advocacy for incremental reforms to the House, and we have found that the majority of members share our appetite for change – but successive Governments have shown limited interest.

I fully support recommendations put forward by the Burns Committee in 2017, which would reduce the size of the House to 600. But recent Prime Ministers have sometimes been profligate with appointments, when we should be operating on a ‘two out, one in’ basis.

I have also welcomed debate on reforms to the appointments system proposed by members of the Lords.

These include:

An end to the award of peerages in resignation honours lists;

Allowing numbers of hereditary peers to fall by ending the system of by-elections to fill empty places;

And increasing the power of the independent House of Lords Appointments Commission to vet prime ministerial nominees for merit and readiness to take part in the work of the House.

One of the strengths of the UK Constitution is that it has been able to evolve to meet new external and internal challenges. Now is a time for evolutionary change.

I have spelt out some of the challenges which I believe our political system faces. I do not claim to have the answers to these challenges. Indeed, I believe that many of the problems can only be made worse by politicians pretending to have quick solutions.

However, my experience as chair of the Commons Treasury Select Committee and a member of the Commission on the Future of Banking which I established following the financial crisis taught me the value of certain principles.

What are those principles?

First, civic engagement – To get the broadest possible range of opinion and insight to inform our proposals for the future of banking, we spoke not only to politicians and advisers, but to bankers, external economists and consumers.

Next, a long-term perspective – We needed solutions which would last and be flexible enough to respond to developments in a rapidly-changing industry.

And last, consensual working – As a Labour MP at the time, I had a deliberate policy of reaching out across the party divide to involve senior members of the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats and ensure our proposals had broad-based support which would survive changes in government.

Often, the obstacle to addressing complex issues is the difficulty we have in working productively together. On too many key issues, we all know the broad direction of travel, but we fail to unite behind taking the necessary steps.

Yet these are core tasks of politics and politicians. We need collaboration, shared learning and action at all levels.

My concern is that a political system driven by five-year electoral cycles and regular reshuffling of ministers can mean that politicians are rewarded for novelty and the appearance of activity rather than the policy stability that delivers long-term gains. The party battle can mean that the work of finding agreement on long-term goals takes second place to the search for “wedge issues” which may deliver a momentary advantage over your rivals.

There is a place for the contest between the parties which characterizes the elected House of Commons. But there is also a place for the consensus-driven approach often seen in the House of Lords. This approach builds the kind of trust which permits open-minded analysis of the choices ahead of us and improves the chance of agreement on the best course of action to take.

Isn’t this a process of education in the broadest sense of the word? In our increasingly fractured society, we need to learn again how to get along despite our differences. Indeed, we need to learn how to prosper from our differences. I think again of Lord Judge, who instead of disparaging opinions which diverged from his own, would say: “How interesting that you take a different point of view on this issue … let’s explore how that comes about and what possibilities arise.”

My conclusion is that the challenges facing us are complex, and it is incumbent on us as politicians to consider not only “what” we need to do, but “how” we should go about the task.

Our approach must involve:

Engaging civil society, so that we learn from devolved and local government, businesses, workers, academics, charities, community organisations.

Taking a long-term perspective, developing programmes that can evolve as technological and demographic change works through.

Shifting our political culture so politicians feel they will be rewarded at the ballot box for tackling the big issues in a sober and meticulous way.

None of this will happen unless we build trust and mobilise consensus. What are the key tools for this task? I can see a few possibilities – but maybe you can add to the list.

Some are structural – for example:

Reforming the House of Lords to boost the credibility of the part it can play.

Increasing the outreach from Parliament to civil society, as Ireland has done with Citizen’s Assemblies.

Making greater use of consultation and pre-legislative scrutiny to ensure bills are fit for purpose. And more post-legislative scrutiny of the kind the Lords undertakes when it looks back at an Act several years after it has become law, to see whether it has had the intended effect. In the new session of Parliament which has just begun, we are establishing two special inquiry committees to investigate how the Inquiries Act 2005 and the Modern Slavery Act 2015 have worked in practice.

Other potential changes are cultural.

This could involve nurturing inter-parliamentary links and mutual respect between Westminster and the devolved assemblies. One of my first acts as Lord Speaker was to visit Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast and establish an Interparliamentary Forum, in which the devolved institutions can speak with the Commons and Lords on an equal footing.

It could mean creating a common narrative which resonates with all our people. Beveridge famously did this in the 1940s when he listed the ‘five giants’ to be tackled by the post-war welfare state – Want, disease, ignorance, squalor and idleness. The threats may be different today, but who can doubt that we face modern giants in the 21st century?

It probably doesn’t surprise you that the Lord Speaker thinks the House of Lords plays a vital role in our Constitution: addressing our most complex issues, exploring with objectivity and building consensus.

As I have tried to set out in this speech, I believe the mission of the Lords is informed by the same values of education that the LSE exemplifies:

A spirit of curiosity and an openness to new ideas. An appetite to seek out evidence and to interrogate it rigorously before coming to conclusions. A respect for learning and expertise as the route to understanding of our modern world.

These are values which have served both our Parliament and our universities well over the centuries. I believe they can continue to be deployed by the House of Lords as it plays its part as a second chamber in helping our nation overcome the formidable challenges which lay ahead.